Mexican visual artist Carmen Mariscal lives and works in London. She works in a range of media but has specifically made three cyanotype prints for The Human Touch catalogue, as part of her essay, ‘On Bound Hands’. Discover more about the artist and the work she has created in connection with this thought-provoking show.

The etymology of ‘touch’ is late 13th century and comes from the Old French verb tochier, its meaning is: "[to] make deliberate physical contact with." Physical contact is something we have all been deprived or restricted of experiencing over the course of the pandemic. How has this restriction of touch affected your art?

As an artist much of one´s work is made with our hands, as viewers* we often feel the need to touch artworks, especially sculpture. That is why I think that the haptic is so important.

For the past 15 months most of our contact with art has been through computer screens, when we do this, our perception of colour, scale, texture and temperature are altered. Everything is in one dimension. When we “touch” art directly with our eyes our other senses wake up and we acquire a deeper level of knowledge of the works.

I remember being a young girl in Mexico City and visiting the Henry Moore exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno with my grandfather. Moore had said that the public could touch his sculptures. That experience has stayed with me forever; my connection with art now goes through my eyes but even if I don’t touch the works I can almost always “feel” them in my fingertips.

In 2020 just before the Covid-19 pandemic, I created the public sculpture Chez Nous, it was located at the Place du Palais-Royal in Paris and built from the recovered gates and padlocks of the Pont de l‘Archevêché. It depicted a house without windows or doors. Chez Nous was conceived as an archetypal space that invited passersby to reflect on the essence of love and the symbol that lovers have chosen to represent it: a padlock. The idea was that the public would be able to touch the padlocks, feel them and thus be in “contact” with the couples that had attached them.

Chez Nous opened to the public on March 12th at 6 pm. That same evening president Emmanuel Macron made the first announcements for the beginning of the confinement period (Lockdown) for France. By March 17 the whole country was on complete (and very strict) Lockdown, with the possibility of leaving home only for essential shopping and the occasional jogging, and always with a special permit and ID card.

Chez Nous was supposed to be viewed (and touched!) by around 800 000 people, at the end only very few could see it in person.

The envisioned viewers for Chez Nous were people coming out of the metro, going to the Louvre, tourists, people going to work nearby and general passers-by. There was almost no public during the first two months that it was up. Chez Nous became a lone symbolic figure in the middle of an empty square and lived in sepulchral silence.

*I used the word viewer but I do not think it is the correct word for describing people visiting exhibitions. The word viewer privileges the sense of sight over the rest. We are never only viewers, we experience exhibitions through our different senses.

Restrictions started to lift and people went to see the sculpture but almost no one dared to touch it, touching it became dangerous, the public could get infected. Not only did this sculpture become a symbol of lockdown in Paris, it also became a symbol of what is outside, that what belongs to a city and to all of us but cannot be touched.

You have created three cyanotype prints in connection with The Human Touch, directly inspired by an object in the exhibition from our collection, ‘Figure with Bound Hands’, Egypt (c. 2160–1650 BCE). What drew you to this object?

One of the exhibition curators, Suzanne Reynolds, had seen images of my exhibition La Esposa Esposada (The Hand Cuffed Wife) and thought that there were many similarities with the ‘Figure with Bound Hands’. I was intrigued by this figure, I did research about it and I spoke to Suzanne Reynolds and to co-curator Elenor Ling to know more about the history of the piece.

When I saw images of the small terracotta figure it reminded me of one of my early series La Novia Puesta en Abimso (The Bride Mise en Abyme). I was particularly interested in the representation of a woman with tied hands and this made me reflect, as I have done in several bodies of work, on women´s situations around the globe where their hands and minds are symbolically bound, where they feel helpless and have no agency.

Are there any other objects in the exhibition that speak to your own practice?

Many! But I think that one of my favourite walls in the exhibition was the one where there was a large photograph of Frank Auberbach´s hand surrounded by prints that he made and a painting. The power of the image of his hand captivated me, it is as if all of the artist's creative force was concentrated there.

I was also fascinated by Marianne Raschig´s work on hand prints of artists, they are a sort of intimate portrait of each person.

Your work explores recurrent themes of memory and fragility. Do you think these themes play into the narrative of The Human Touch?

Very much so. Memory is present at different levels, firstly and maybe the most important: the memory of touch that is alluded throughout the exhibition, not only in the works presented but in the display itself. Human beings remember what they have touched with their bodies and with their eyes, and we keep that stored consciously or unconsciously. Then there is the historical memory embedded in the paintings, manuscripts, videos, photographs, sculptures and drawings.

Fragility is present throughout as well, many of the works exhibited are precious and fragile themselves and have to be presented under glass. Watching all the images of hands reminded me of how strong but also how fragile our hands are, they are our main working tool and because of this they get exposed and can be injured or cut.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, even the pieces in the exhibition that could have been touched cannot, this reminds us also of our own fragility as human beings, we can get ill by touching, we are fragile.

In your essay ‘On Bound Hands’, you state that the reason you chose to make cyanotypes was “to bring them, [the imagery], all into one single historical moment: Now.” Why was this important to you? Was this decision influenced by showing the work in a museum?

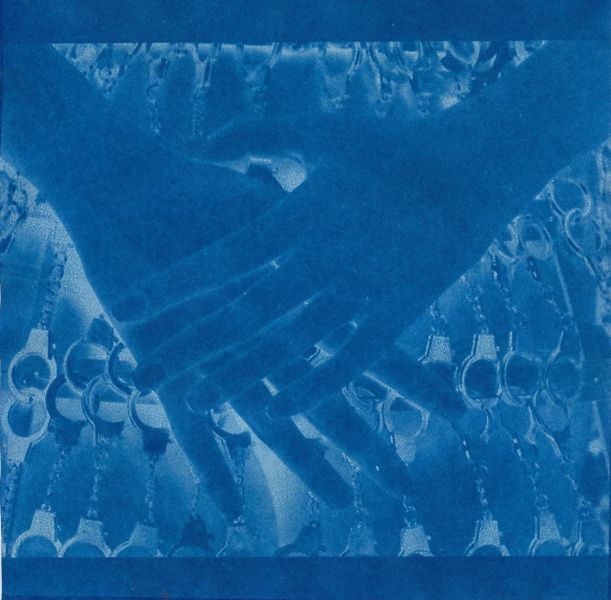

I created three cyanotypes for the exhibition as a dialogue with the Egyptian sculpture. Due to the pandemic, I could not see the statuette in person so my first contact was through images on the computer that I later printed out. As I could not see the piece physically, my perception of the sculpture´s size, texture and colour was altered. The dialogue created with ‘Woman With Bound Hands’ was not with the sculpture itself, but with its photographic flat image.

I had a physical need to work around the sense of touch and smell, so I applied chemicals to small sheets of paper and worked on the cyanotype process. I made dozens of cyanotypes using images of my own work and of the ‘Figure With Bound Hands’, bringing them all to one single historical time, now.

Cyanotypes use sunlight to be developed. It was important to me to use this early photographic technique to expose images from different periods under the same 21st Century sun, and to draw attention to situations that women still endure today and have had to endure for thousands of years in patriarchal societies.

The three prints presented were created in the same size and technique, all are representations of women with hands tied or trapped.

You also state in your catalogue essay that: “around the world, many women´s hands may not be bound physically but they are symbolically.” Could you expand more on what you mean by this?

It is mainly through our hands that we touch, hands symbolise touch but they are also our tools for creation, for freedom. When we see images of people whose hands are tied we immediately think of prisoners.

While I was working on the exhibitions La Esposa Esposada 2018 and Calladita Te Ves Más Bonita 2019-2020, I interviewed over 100 women of different origins. In the first project I asked them to talk about marriage in their countries, in the second one they spoke about things that they were told not to say.

Working on these two projects made me realise that even today in the 21st Century many women around the world are not free to create and live their own lives, they have no agency, they are still bound to the explicit or hidden laws of patriarchy.