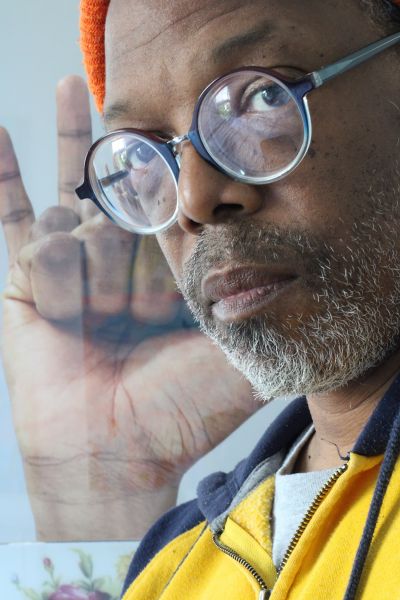

Richard Mark Rawlins was born in Trinidad & Tobago, and currently lives and works in Hastings, UK. For The Human Touch exhibition, Rawlins shows his work Empowerment (2018) and has contributed to the exhibition’s catalogue with his essay, ‘A Show of Hands’. Find out more about the artist and the context of his work.

Throughout the global pandemic, our hands have never been more scrutinised from how we wash them, to what we touch, and how we use them to communicate with one another. Has this new focus on our hands given your work, Empowerment (2018), new meaning?

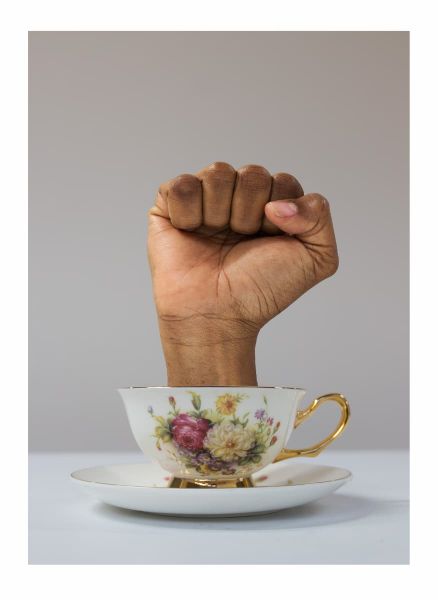

I think it would be disingenuous to say that the Global pandemic gave new meaning to the work, as its roots are in the research of an essay by Professor Stuart Hall: “Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities” (1991). This is not to say that new meanings can’t be developed around the work, as all work is open to interpretation. The work is shaped largely by the notion of English Identity and what that means if tea, sugar and the migration of people of colour are added to the mix. Masterfully put, in Hall’s assertion of identity, he inserts himself as the sugar in the bottom of the English cup of tea, saying that that there are others in the cup beside him. I have always seen Empowerment from the perspective of a symbol for something and what that something means, hence the titles Acknowledgement, Empowerment, Resistance and The True Crown. It’s about the expression of human agency and self-determination.

Along with the Global Pandemic, though, came the global summer of protests, sparked by the killing of George Floyd in the US, and as people came to a reckoning with that moment and what it meant, it would be equally disingenuous to think that the work in that moment would not take on new meaning.

My friend, Dr. Carol Ann Dixon, put it this way: “To me, the raising of a hand has always signified so much more than one person seeking permission to speak in a space where power seemingly appears to reside outside of themselves. Permission-seeking from whom? The act of choosing to raise one’s hand is always a symbol of agency, as opposed to deference – clearly signifying that someone is actively taking control and giving the target of their attention – as well as onlookers – no other option but to look in the direction of the raised hand and respond.”

How does your work explore the exhibition’s theme of touch?

My work is symbolic. I think in pictures – it’s how I make sense of what I read and the world around me. What does the clenched fist mean and imply? I think that symbols are designed to invoke, like physical touch, certain responses, and much like physical touch, certain emotions. So the notion of touch as a theme is symbolic in my work. For example, some patrons at the 2019 exhibition, “Get Up Stand Up Now”, saw Empowerment as a statement of resistance to otherness. Some people bought postcards of the work and have it at home as a cherished object. When someone makes a work, they can only hope that it evokes some sort of connection or personal resonance, a story or a memory. Beyond that hope, artists have no real control, bar establishing a definitive supporting text of finality around the work. In 2020, the symbol of the fist became a way of presenting solidarity for some people. In lieu of Black Squares being posted on social media during the George Floyd moment, quite a few people of colour posted Empowerment, and even actress Emma Watson who alongside sharing the image, noted: “One thing we can all do to honour the struggle for racial justice in the US is to interrogate, understand and dismantle the racist structures of our own countries.” Empowerment has come to embody so many things to so many people.

Empowerment (2018), sits within ‘The Power is in your Hands’ section of the exhibition and is adjacent to Rodin’s Grande main crispée (Mighty hand). Do you think there is a dialogue between the two pieces?

There most definitely is a dialogue between the two. One look at Grande main crispée (Mighty hand) almost makes that point. That outstretched hand, full of all its power and frustration, like Empowerment, is unbound. Neither knows shackles. They are both speaking for themselves and both hold agency. As it is put in the catalogue, the outstretched hand supports those in need, reaches out across divisions, and seals the bond between individuals, communities and nations. Both hands, raised and upright, assert identity and a very real sense of political power.

Your essay ‘A Show of Hands’ discusses your body of work ‘I Am Sugar’ and the inspiration behind it, specifically referencing the essay by cultural theorist Stuart Hall ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’ (1991). Do you think showing Empowerment (2018) not alongside the rest of the series encourages the viewer to reflect upon race more, especially given the historical and contemporary context of a black hand making a fist gesture?

Well it’s the thing about the black body in any space where it isn’t part of a majority ethnic group, isn’t it? You can’t miss it, and you can’t ignore it. Race is that uncomfortable reality that some call a ‘social construct’, a made-up thing; some claim to not see it, some use it to weaponise, some use it to shut other people up, some use it for justifications of moral opinions they like to call truths in pursuit of cosmic justice or for things they wish to sell or to steal, divide and conquer. The works are meant to work together like movements in a symphony or acts in a play, but each can stand on its own. The fist has often been seen as a sign of militancy and aligned to revolutionary groups and movements for change. There is power in its assertion, figuratively speaking. But when we bring race into it, we have no choice but to begin the uncomfortable discussions.

I am a black man. I know my own self the most, and hence, centre myself in the work by the use of my hand, in much the same way Hall figuratively centered himself in the essay. The viewer can’t help thinking about race in a society like this where so many are othered. The reception of this work in another society, a society of majority people of colour, for example, might be less about race and more about power and the historical and contested realities of colonialism. I could also have made this work if I were a member of the South Asian diaspora… as Hall said, there are others in the cup beside me. In direct relation to Trinidad, where I’m from, it would have spoken to the plight of the indentured labourers who were brought to the Caribbean after Emancipation to carry on sugar manufacture.

Does showing in a museum, as opposed to an art gallery, change the way in which your work can be viewed? Particularly in a University owned museum.

I really like the idea of my work showing in museums and in conversation with other works as opposed to an art gallery. But ultimately, it depends on the curatorial agenda and the narrative built around the works in the exhibition. I moved to the UK to have the opportunity to expand my networks and increase the dialogue around my work, and in a very real sense I have found some of that in the curation of this exhibition, and the exhibition’s programming engagements. These are important in any artist’s career, and most certainly in mine. Being engaged in the progress of the exhibition, the writing of an essay for the superb catalogue, discourse around the work, and being a contributor to the book club earlier this year, are moments I cherish that have filled me with pride. I think it is the thing that we all search for…the ability to make a contribution and have that contribution be taken seriously.

Is there a specific object in the exhibition that speaks to your own practice?

Donald G. Rodney’s My Mother, My Father, My Sister, My Brother*. Rodney’s use of the ‘self’ via his own skin to examine familial lineage, home, the legacies of the slave trade and his own sickle cell anemia as a metaphor for British society creates a work that is true, direct and relatable to so many on so many levels.

Do you think Lockdown has changed the way the public approaches art?

Lockdown has certainly changed our tolerances to art. There are new forms of viewing being invented all the time. There are now portals, VR platforms and even video game-like virtual galleries (some of them pioneered by commercial galleries and art fairs) all in the name of presenting exhibitions now. Not all of them work. There are some galleries, like Hastings Contemporary, that even went so far as partnering up with a robotic firm to create a drivable robotic tour of its galleries.

I have missed seeing people viewing my work in physical spaces though. One key and memorable moment for me will always be walking into the ‘Motherland’ section of “Get Up Stand Up Now” and seeing people gathered around Empowerment with their smartphones taking pictures of the work. What these initiatives have shown is a certain insistence on not giving up and continuing in spite of it all. I tried booking a weekend tour of the RA summer show … I couldn’t. It’s all booked up. That show isn’t until September and I’m writing this in June. I tried booking the opening weekend of “The Human Touch '' and I’m an artist in the show, same thing for Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Tate … all booked up.** Yeah, the public knows what it missed, and it’s making use of every opportunity.

* The postponement of the show’s opening from 6 January to 18 May sadly meant that this work, which was promised to another exhibition for the summer, is no longer on display in The Human Touch.

** In 2020 the Fitzwilliam Museum acquired a set of ten etchings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye called ‘First Flight’ (2015), P.96-2020. You can read more about them on the UCM blog

Sign up to our e-news to find out when they will be on display.